Julian Priester

A fount of knowledge for the jazz community, the trombonist and living legend is shaping the next generation of Seattle musicians.

The Seattle rapper keeps his memories of the Central District alive with vivid lyrics and a jazz sensibility.

by Kemi Adeyemi / June 1, 2022

You would never guess, given all the work that he’s put into it, that Porter Ray Sullivan never set out to be a professional rapper.

Porter Ray (his stage name) grew up in a musical family in the Central District, where his parents had a vast record collection. He would study the albums, poring over the liner notes to learn the names of the writers, producers and musicians behind the sounds that were always playing in the house. His parents helped attune his ear to the original songs that hip-hop producers were sampling in the contemporary songs he heard on the radio. “They hear ‘Hypnotized’ by Biggie,” he recalls, “my mom would be like, ‘You know, that sound right there is from this David Bowie record — let me play this for you.’”

Rap was a revelation for Porter Ray. He remembers a pivotal moment from his childhood when his cousins played him “Funkified” by Da Brat. “It just blew my mind,” he recalls. By the time he was in middle school at St. Therese Catholic Academy, Porter Ray was spending countless hours transcribing, memorizing and rehearsing the raps he listened to on the radio, showing up at school ready to perform. “That was like my early training in being an MC,” he recalls. “I started being able to take pieces of those verses and writing my own stuff, or just learning how to develop my own rhyme patterns and wordplay.”

His early interest in writing poetry and short stories came into play when he began writing his own lyrics, which he practiced delivering with friends. “We would kick rhymes over the internet, or just over the phone,” Porter Ray says. “All the time, we would just be rhyming to each other.”

Now 34, Porter Ray was an eager student of the creative arts, but he never had a particular goal in mind when it came to his relationship to music. “Rap was like my friend when I was younger,” he explains. “It was someone I could listen to, someone that would talk to me and sort of understand me, and help guide me.”

His perspective changed after a series of losses made him think differently about the skills he had been quietly developing. When Porter Ray was 16, his father died after a four-year battle with multiple sclerosis. Then, in 2009, his younger brother was accidentally killed amid a neighborhood dispute.

“I eventually felt like I had this story to tell and these people that I wanted to honor. I saw my neighborhood changing and gentrification starting to take place. I lost my little brother, friends being incarcerated,” he recalls. “So I'm … feeling like I need to tell this story, and hoping that I could also connect with people, too.”

Starting in 2013, he released several mixtapes and an EP before making his Sub Pop debut with Watercolor in 2017. (The label promoted the album as a “natural extension of musical traditions that have poured forth … from the rich soil that is Seattle’s Central District.”) Porter Ray followed that success with Eye of the Beholder in 2018, and two years later, he released When Words Dance, a jazz-inflected collection that earned a spot on The Seattle Times’ best local records of 2020. Together, this body of work forms an ode to the Black community that surrounded him in the Central District. The music is also a lamentation.

“To be around a lot of Black people in my youth, in such a beautiful place with heavy community involvement — an art scene and community centers, sports and athletics and events — all these things were, for me, just the most important things when I was younger,” he says. “It's been difficult to see all that get wiped away.”

Porter Ray keeps the Black life of the neighborhood alive in detailed raps that explore the people and places that have shaped him. “I try to … immortalize the people and places and the feeling that I had growing up there,” he says. He covers topics from mundane conversations between friends getting high and driving around town to love stories (as in “Black Cindy Crawford” off of 2013’s RSE GLD) to stories about the causes and effects of senseless gun violence. In “Daily News,” from When Words Dance, Porter links gun violence to greed — not only on the part of the shooter, but also the media outlets that profit off of coverage of this violence.

His music traces and elucidates the feeling of being in community — how it is expressed in small moments of grief and growth with the family, friends, and lovers who he name-checks throughout his songs.

These narratives are enlivened by Porter Ray’s effortless, lilting cadence, which softens the hard consonants characteristic of West Coast rap. The compositions backing his words blend steady bass lines with ethereal keyboards that build space for his words to linger. “Jazz-influenced, nostalgic, ’90s hip hop is what I gravitated to,” he explains, “and that was the sound that I chose to try to emulate and try to push farther.”

The sonic compositions on top of which Porter Ray rhymes recall the city’s history as a midcentury jazz mecca — an era in which he is well-schooled. “You hear about Ray Charles coming through here and studying under this cat Bumps Blackwell,” he says, “who was helping arrange records for Little Richard; he was helping Ray Charles, I believe he was helping Quincy Jones. And then hearing about Quincy Jones and them guys really sharpening their tools here.”

Seattle’s Black jazz scene faded as musical tastes changed — decades later Seattle would become known primarily for its grunge and indie rock — and as Black people were priced out of neighborhoods like the Central District, which made Porter Ray who he is. “I feel like it's been a fight between us as Black people and the city, a fight for our own identity in a lot of ways,” he says. “Because if we don't have our neighborhoods — we don't have our villages that we grew up in. Everyone's sort of dispersed. It makes it tough to continue to represent a city that you feel like is working avidly to wipe you out.”

But Porter Ray is encouraged by the community of artists he is embedded in, and heartened by how local hip-hop and R&B artists are investing in one another. “I see them working together a lot, and us working together a lot,” he says. “I see connections between different neighborhoods, whether it's the CD and the south end, or Seattle to Tacoma.”

His music is helping to foster this unity, as it weaves in the voices of other Seattle hip-hop and R&B artists, including Shabazz Palaces, Cashtro, Stas THEE Boss, Nate Jack, JusMoni and others — several of whom join Porter Ray as part of the Black Constellation artist collective. Porter Ray’s music is a product of these collaborations, and their collective work is a living testament to the ongoing presence of Black life, community, neighborhoods and music in Seattle. “I see a lot of unity within the artists,” he says. “That’s one thing I do think is beautiful about our scene.”

Black Arts Legacies Project Editor

A fount of knowledge for the jazz community, the trombonist and living legend is shaping the next generation of Seattle musicians.

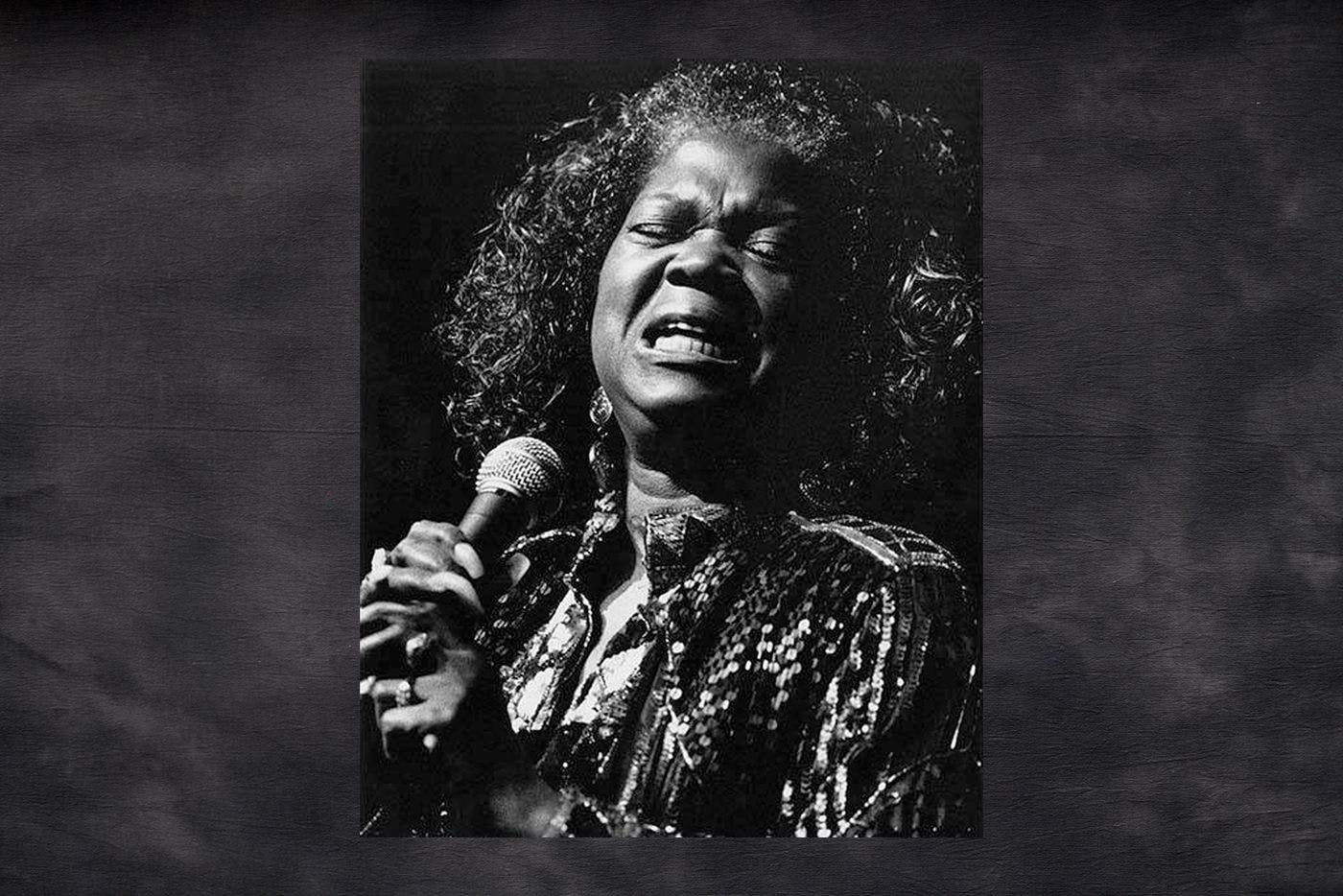

With a voice like ‘honey at dusk,’ the singer helped put Seattle’s early jazz and blues scene on the map.

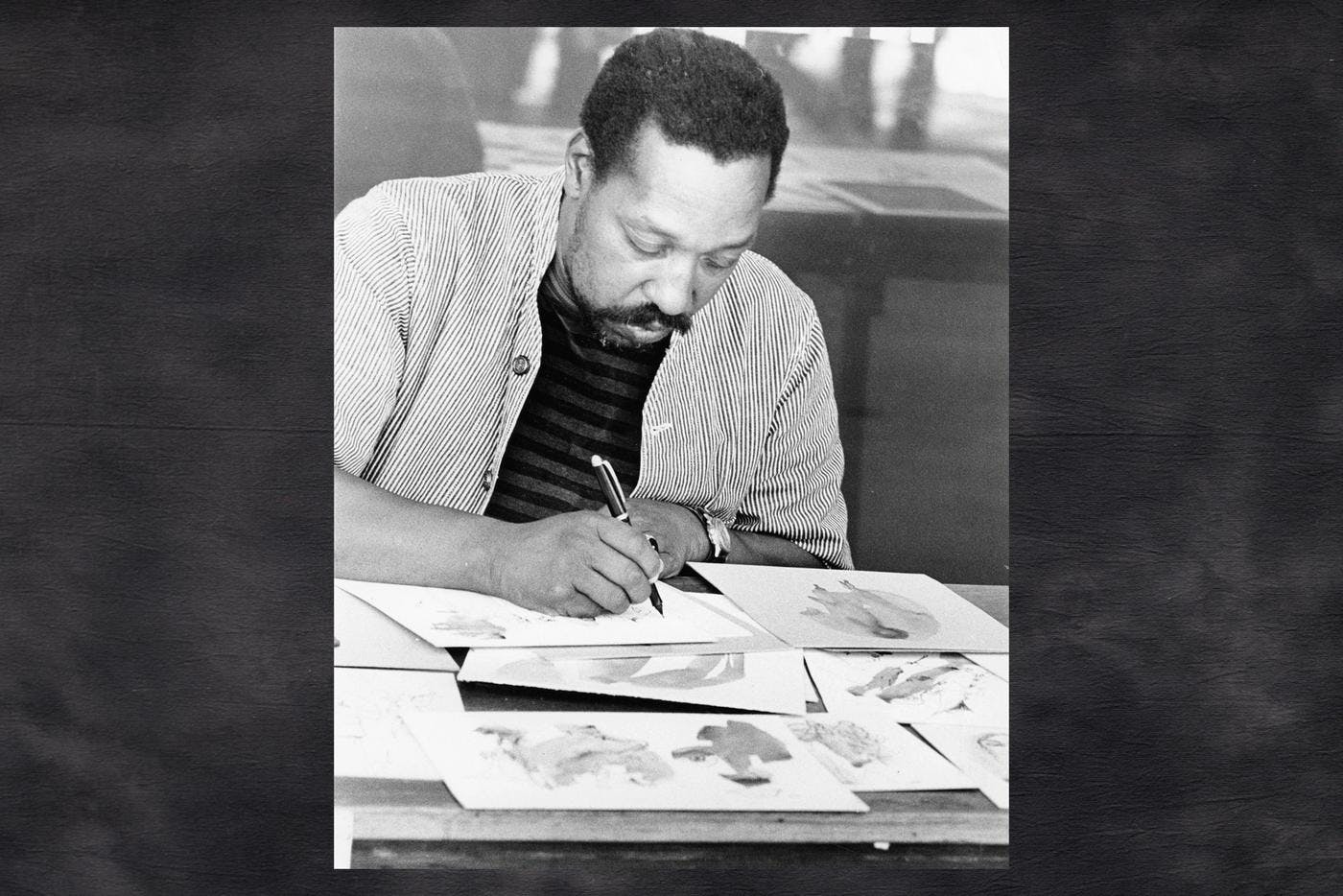

The first Black art instructor in Washington was an experimental artist ahead of his time.

A poet at heart, this soul singer/songwriter is inspiring the next generation of Seattle musicians.

As a founder of Digable Planets and Shabazz Palaces, the Seattle rapper has pushed hip-hop to the outer limits.

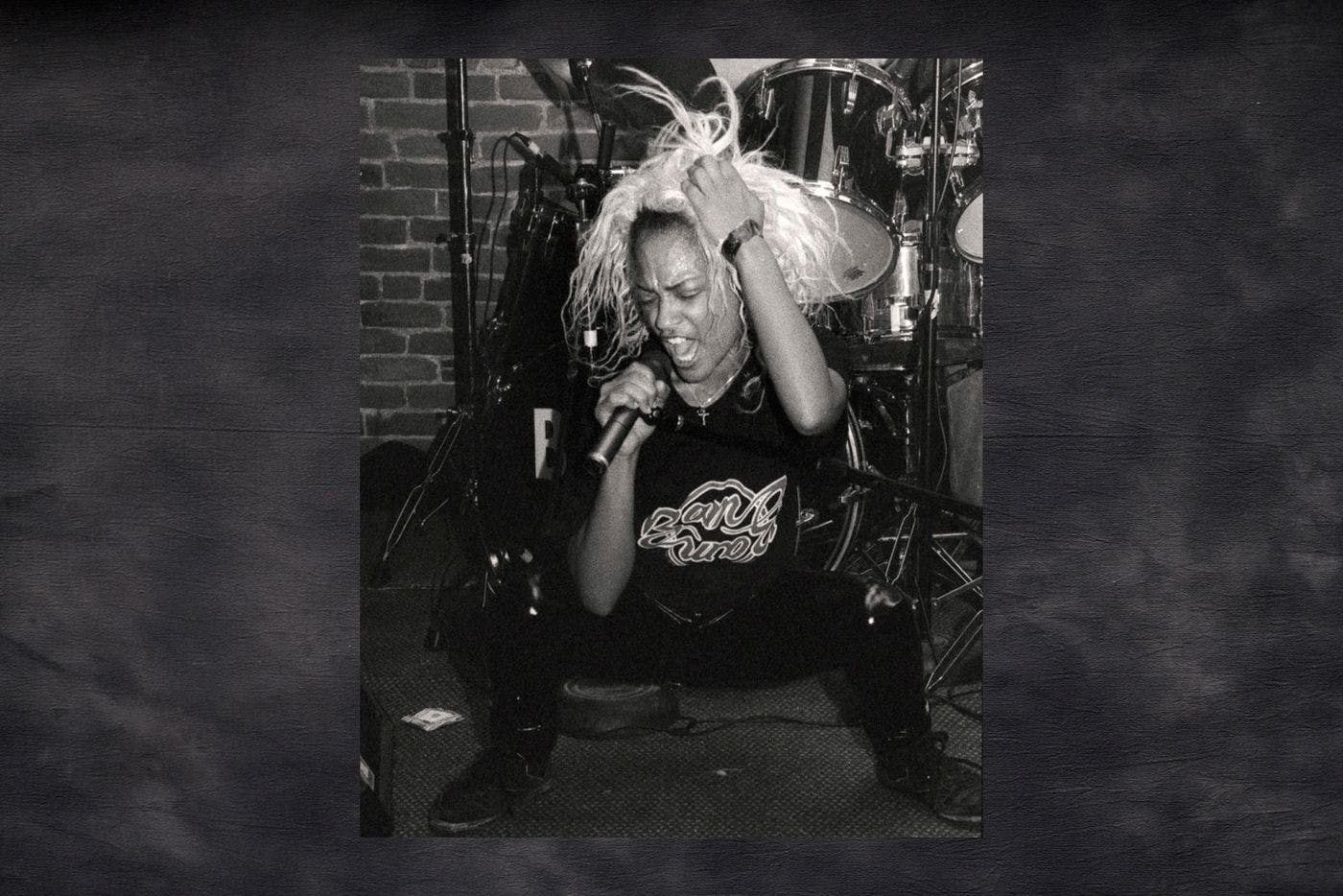

A pivotal figure in Seattle’s proto-grunge scene, the Bam Bam singer has been long-overlooked. Now, rock history is being rewritten.

The talented multi-instrumentalist uses music to string communities together.

Meet a Seattle music pioneer and the band carrying the legacy of Northwest rock forward.

Thanks to our Sponsors

Your support helps Crosscut create projects like Black Arts Legacies. Learn how you can help with a one-time donation or recurring membership.

Support Crosscut